Rebuilding Lives in Brazil

Hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants from Latin America, the Caribbean, and around the world are reestablishing themselves in Brazil. An innovative housing and employment program in São Paulo, implemented with private sector support, offers a model for inclusion.

Javier Muñoz Mata hardly notices the sharp tang of sawdust that hangs in the air of a small workshop in downtown São Paulo, Brazil. As he fits a metal hinge to the cabinet he has just constructed, drilling it in place with the deftness of an experienced woodworker, he glances at the long to-do list taped to the wall beside him. The stacks of partially-completed cabinets reach almost to the ceiling; the piles of glinting hinges hint at busy workdays ahead.

Muñoz doesn’t find it daunting. In fact, this is exactly what he hoped for—dreamed of—for years. A good-paying job wasn’t possible in Venezuela, where he was born and raised, so in 2019 he and his wife Estéfani, both in their mid-twenties, made their way to Brazil. Days after crossing the border, they received the necessary legal paperwork, work permits, and other support. The couple settled in São Paulo, the southern hemisphere’s largest city, because they thought they would have the best chance to find jobs there.

“We don’t want to depend on anyone,” he says, perched on an upside-down crate in a corner of his workshop. “We just want a chance to work.”

When Muñoz and his wife first arrived in Brazil, they hoped to earn enough to help their parents, siblings, and other family members leave Venezuela, and they sought enough financial stability to have children, too. But he couldn’t have anticipated what would happen in São Paulo. He was selected to participate in a pilot program to train refugees to be woodworkers—and then he was hired to help renovate a 74-year-old downtown São Paulo building, known as the Chrysler Building, that was abandoned a decade ago. Through a partnership with IFC, the Chrysler Building will offer 3 to 5 percent of its apartments at a discounted rate, with sliding-scale rental fees to migrants and refugees.

“Having this job gives me a deep sense of satisfaction,” Munoz says. “To be part of bringing this building back to life for other refugees to live in is more than I could have imagined.”

It took a lot of imagination to shape a project like this and steer it forward, concedes Isadora Rebouças. She is the founder and CEO of Citas, a São Paulo real estate consultancy that recovers unutilized buildings—the Chrysler Building among them—in the city center.

“We’re trying to solve a big problem,” Rebouças says, standing on the balcony of a top-floor model apartment in the Chrysler Building and scanning the downtown skyline.

“Actually, we’re trying to solve two, three, four, five problems, too many to count,” she corrects, pointing to the many abandoned structures nearby.

These once-grand buildings are not just uninhabited but in a state of decay, with pockmarked, peeling plaster covered in graffiti and gaping holes where windows used to be. Many of them, like the Chrysler Building, are architecturally significant midcentury modern structures that conjure a vision of downtown São Paulo’s prosperous past.

For Rebouças, looking out from the balcony, they offer a glimpse into a promising future.

“Why would we want to tear these down?” she asks. “Why is that better than retrofitting the existing buildings? The city needs affordable housing, and places for refugees and migrants, and more jobs for everyone. We have multiple issues that need solving. But I couldn’t do it alone. I’m not an engineer or a humanitarian worker. I’m not a city official. I’m the one with the spreadsheet.”

Collaboration with IFC offered a way forward. Early on, this cooperation helped finance IFC’s EDGE green building certification program for the retrofit; this supported the achievement of a minimum of 20 percent reduction in water, energy, and embodied carbon in construction materials. Cooperation with the UNHCR Brazil office made it possible for refugees and migrants with an interest in woodworking to receive training to become carpenters. (UNHCR is the UN Refugee Agency.) Some of those refugees and migrants, like Muñoz, were hired to create furniture for apartments in the Chrysler Building. Later, the global IFC-UNHCR Joint Initiative also supported the project.

As the Chrysler Building readies the apartments for its first tenants, Rebouças is barely pausing to mark that milestone. That’s because Citas is not just demonstrating whether this one building can meet business and sustainability objectives while serving a social need, she says. Citas and the other partners aim to prove this model can be applied throughout downtown São Paulo and in other cities around the world that need to employ large refugee and migrant populations, supply affordable housing, and revitalize urban areas.

“It’s heartwarming to see this building come back to life, especially to be able to employ refugees and offer them a place to start new lives,” Rebouças says. “But this is just the beginning.”

Changing the narrative

Pioneering projects like the Chrysler Building answer an urgent need, according to Makhtar Diop , Managing Director, IFC.

“Throughout the world, the inclusion of refugee and migrant populations in host countries is challenging as no single actor has the capacity, experience, and resources needed to implement it alone," Diop says. "The collaborations bringing the Chrysler Building back to life demonstrate how to link social and sustainability needs with business solutions. This bold thinking has led to a groundbreaking pilot program that can be scaled up and replicated worldwide. This is exactly the spirit of the IFC-UNHCR Joint Initiative, and I’m encouraged to see it delivering results for displaced people and host communities alike.”

It was far from obvious that a project like this could work, according to Maria Beatriz Nogueira, head of the UNHCR field office in São Paulo. Nogueira remembers her initial surprise when the project was proposed to her.

“We’re used to seeing social projects that have a business component, but this was a social project within a business model, and it was totally new to us,” she says. “We hadn’t seen anything like this before.”

Nogueira was open to the idea because it promised a new way to think about an old problem. “We have an opportunity to change the narrative—to show that refugee housing is more than emergency short-term shelters,” she says.

Flipping that script was necessary because of the surging numbers of refugees, migrants, and forcibly displaced people around the world and in Latin America and the Caribbean, a region experiencing “the worst migration crisis in its history,” notes the World Bank.

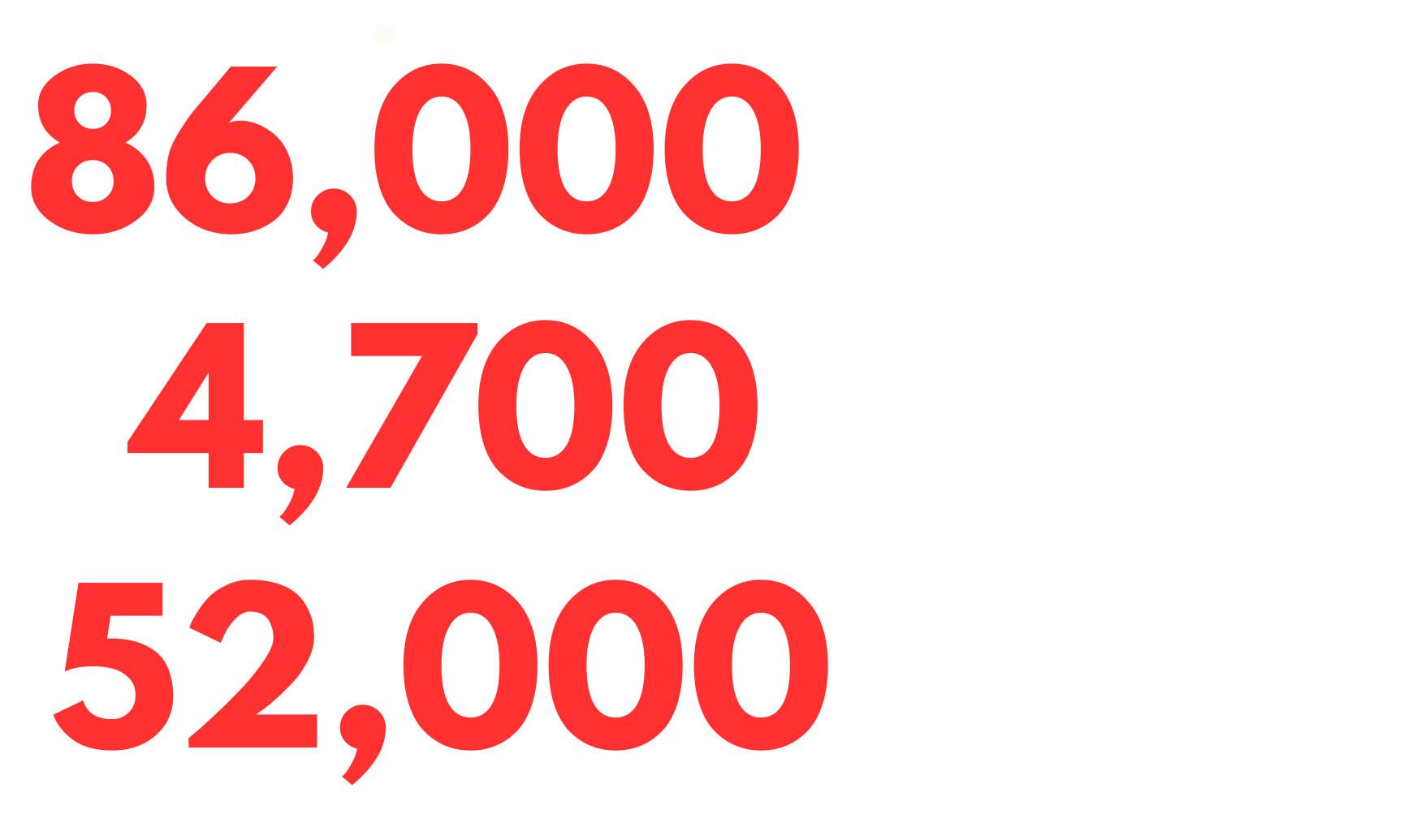

The figures are formidable.

As of September 2023, more than

people around the world were forced to leave their homes due to armed conflict, persecution, or serious human rights violations, according to UNHCR.

In Latin America, the largest recent exodus of people comes from Venezuela. By June 2023, more than

had left the country in search of international protection and better living conditions. Brazil is the third most popular destination country for Venezuelans in the region; 450,000 refugees from Venezuela now live in the country.

Brazil also hosts

Brazil’s 1997 Refugee Act is the most progressive in the region; legal experts have called it "a model refugee law" for Latin America.

For refugees who settle in São Paulo, housing and jobs are the two most pressing concerns, according to Nogueira. But São Paulo— a megacity already straining under a population of nearly 12 million people, with among the highest levels of income inequality in the world—has an “affordable housing crisis,” says José Police Neto, Undersecretary of Urban Development and Housing for the São Paulo Municipality.

In São Paulo, 52,000 unhoused people live in encampments or in tents, and the city’s homelessness rate is four times higher than in Rio de Janeiro and 4.7 times higher than in Belo Horizonte, the second and third cities with the largest homeless populations in the country.

“Empty downtown buildings are a gigantic asset” in confronting the challenge of housing refugees, migrants, homeless people, low-income families, and others who want to live in downtown São Paulo, Neto believes.

He cites the effectiveness of legislation signed 10 years ago that promotes the conversion and use of downtown São Paulo buildings as residential units. The legislation mandates that owners of property that has been empty for more than one year must prove its use or it will be taxed double. This has expropriated 3 million unused square meters from owners and the proceeds from the sale of these properties have been invested into retrofitting other properties, Neto notes. Buildings that remain abandoned for five years will be sold and will generate revenue for the state.

“Responsible legislation generates sustainability,” Neto says. “Municipal authorities want to see squares and public areas live again, but this cannot be done by government or private hands alone. The state’s partnerships with the private sector also can help, like this model with the Chrysler Building, which needs to be replicated.”

Refuge in the City

In 2018, around the same time that Citas began looking for ways to bring abandoned buildings back to life, UNHCR and IFC partnered in Brazil to support refugees and migrants. IFC’s goal was to encourage private sector participation in the areas of employability, affordable housing, and financial inclusion, according to Carlos Leiria Pinto, IFC Country Manager in Brazil.

“Interests aligned in all three areas,” Pinto remembers. “Bringing together the private sector and social organizations was a winning formula because our goals complemented each other’s.”

UNHCR and IFC began collaborating with Citas in 2021. By helping Citas move forward, UNHCR found a new way to help refugees and migrants rebuild their lives in Brazil.

Together with IFC, the São Paulo office of the international refugee agency launched the “Refuge in the City” project, a carpentry and hospitality job training program for refugees and migrants. Caritas Arquidiocesana de São Paulo, a local UNHCR implementing agency, selected the participants, supported course registration, and facilitated participation through stipends to cover transportation and food costs.

Seventeen people from Venezuela, Cuba, Angola, Morocco, and Colombia took the three-week course led by Lab74, a design school. Graduates received a basic tool kit, a certificate, and work materials, as well as help opening a bank account and registering as an Individual Microentrepreneur. All of the graduates received help finding job opportunities, and some, like Muñoz, were hired by Citas.

Transforming the commercial building into 283 furnished, affordably-priced residential units has been a challenge, Rebouças says, but Citas believes in its strategy of customizing its apartments and offerings to the market it serves.

“We know our audience, and we’re developing a product for people who already want to live [downtown],” she says. “They want to be within walking distance of public transportation so they can get to their jobs, and they need low rental rates. We can offer that, while still charging market rates, so that it is a financially sustainable and replicable business in the long run. We don’t have to hope things can be better—we know they can be.”

Muñoz is confident things can be better, too. While he hammers together furniture for the apartments, he thinks about the residents who will be opening the cabinets he has made or placing their phone on a nightstand he constructed.

“I imagine the people living there, and I think they will be happy,” he says.

As for Muñoz, that “deep sense of satisfaction” he gets from his job now extends to his personal life, too. He was recently able to help his brother and other members of his extended family leave Venezuela and join him in Brazil. And now, Muñoz and his wife Estéfani are expecting a child—their “Brazilian baby,” he says, smiling.

The pilot project with Citas is funded by the Comprehensive Japan Trust Fund (CJTF).