Mexico's Blueprint for Green Buildings

By reimagining the design, construction, and operation of buildings, a sustainable housing developer reduces greenhouse emissions while creating investment opportunities–and a better quality of life for families.

Until last year, Armando Suarez lived his entire life in Ecatepec, a chaotic jigsaw of poor hillside neighborhoods that makes up Greater Mexico City’s largest municipality. Stretching north from the city’s limits, Ecatepec is a warren of informal magenta and turquoise block homes, stacked like Lego pieces and perched precariously, one on top of the other, on steep, ragged hills.

But thanks to a unique sustainable housing initiative, Suarez and his family now live in Real Navarra, a quiet, affordable, gated community situated 60 kilometers northeast of Ecatepec. Suarez’s new two-bedroom home provides distance from the gangs that roamed the streets of Ecatepec, and respite from the piles of trash that grew outside his door. Built with low-carbon cement, the home is climate-friendly too, allowing Suarez and his wife, Gabriela, to save on electricity and gas costs.

“The difference between living in Real Navarra and living in Ecatepec is defined by order and cleanliness,” said Suarez. “In terms of electricity and gas, I am saving [money] because in Ecatepec the electrical system was disrupted. Here, in Navarra…my home has a solar heater and that helps a lot.”

In Mexico, where instances of extreme heat and episodes of drought are increasing, sustainable, affordable housing initiatives are in high demand. Real Navarra answers the call while challenging long-held assumptions of the traditionally built home. But Real Navarra is one answer among many: with more than nine million square meters of green certified buildings, Mexico has become a beacon for sustainable construction across emerging markets.

These new initiatives can’t come soon enough. Unless decisive action is taken, emissions from construction are on a path to rise by around 13 percent globally by 2035, according to a new International Finance Corporation (IFC) report on building green in emerging markets. The report analyzes the investments and policy actions needed to reduce carbon emissions in construction value chains in emerging markets and explores the costs and availability of technological solutions to get us there. Mexico is an excellent case study for the report’s findings, illustrating how a major shakeup of the construction sector – and the way we design, build, run, and retrofit buildings – is both necessary and achievable in emerging markets.

In practice, as the report suggests, that means electrifying existing buildings with non-fossil fuels and using specific materials to reduce energy consumption, such as reflective painting for rooftops and film coating for windows. For new buildings, it means using energy-efficient and resilient designs, renewable energies, and district cooling and heating systems. For construction materials, especially cement and steel, switching to low-emission processes, raw materials and fuels, can also reduce emissions now.

“If we design, construct, and operate buildings in a better way while also enabling access to climate-friendly capital markets, those practices could yield a 12.8 percent cut in emissions from 2022 levels and generate $1.5 trillion in greener buildings and materials in emerging markets over the next decade,” says Makhtar Diop, Managing Director, IFC. “This would mark a big breakthrough in the fight against climate change and the ever-increasing extreme weather events that exact an ever higher economic and human cost on the world’s poorest populations.”

How green houses improve lives in a Mexican valley

Nestled in a valley beneath the shadow of the Pachuca mountain range, Real Navarra, run by Mexican property developer Vinte, is a haven of smart townhomes painted fawn and beige, interspersed with green parks and playgrounds, and surrounded by lavender hedges and fragrant begonias. On corners of the development’s wide boulevards, residents pop in and out of tidy supermarkets, a bakery, and laundromat. The atmosphere is cheerful, calm.

Selma Montiel Lōpez moved to Real Navarra five years ago seeking freedom from the din of Pachuca’s chaotic city streets. Tired of the noise and pedestrian traffic created by a gaggle of street vendor stalls pitched outside her door, Lōpez rarely ventured out. Now, living in a gated subdivision street, she and her four-year-old daughter, Karen, can come and go as they please.

“Living in Real Navarra has changed our lives,” says Lōpez, who works as a financial adviser. “I feel safe. My daughter feels safe. She can go out and play outside in the private area and in the parks.”

Selma Lōpez, who has lived in Real Navarra for five years, explains the benefits of living in her green subdivision.

Like Suarez’s home, a few streets over, Lōpez’s two-bedroom house is built with low-carbon cement and incorporates passive design techniques. The trim, cheerful home is EDGE-certified. (EDGE is a building certification system operated by IFC that accredits a development or building as sustainable construction.) Reflective and insulated roofing ensures that the home is cool in the summer and warm in the winter while high-efficiency water, gas, and heat systems keep the bills down.

“Where we lived previously, we paid an electricity bill of 700 pesos (about $39),” says Lōpez. She paid the equivalent of $70,000 for her home backed by an affordable mortgage. “Today, we pay around 200 pesos. For water, in the previous neighborhood we paid 350 pesos. Now, we have great savings by paying only 130 pesos every month.”

Lōpez uses the money she saves on utility bills to take Karen – a diminutive, beaming bundle of dark curls and charcoal eyes – for special outings to the movies and Friday night dinner treats.

Concrete steps towards low-carbon homes

Construction value chains account for about 40 percent of energy and industrial-related CO2 emissions globally, according to IFC’s new report. More than two-thirds of these emissions are from emerging markets. That’s why how buildings are designed and operated will be critical in the next decade, says Rene Jaime Mungarro, co-founder and CEO of Vinte.

Rene Jaime Mungarro, co-founder and CEO of Vinte

Rene Jaime Mungarro, co-founder and CEO of Vinte

As the first and largest housing development in the world to receive EDGE certification, Mungarro says that Vinte’s more than 14,000 green homes save an average of 32 percent per home in energy costs and have a a 67 percent average reduction per home in energy embedded in materials.

These savings are critical in attracting not just environmentally conscientious homeowners but in driving low-carbon economic growth across Mexico, especially in the construction value chain.

Key to stoking that demand is the availability of low-carbon cement and green steel. Cement – the main ingredient in concrete – is the essential building block of most construction projects around the world. While cement is an intrinsically low-impact material, with fewer emissions than iron and steel, overall it contributes to 8 percent of man-made CO2 emissions because of the staggering volumes that the world uses. Nearly four tons of concrete – a mixture of cement and other aggregates – is produced per person per year on average.

Rene Jaime Mungarro, co-founder and CEO of Vinte, explains how companies like his can help create greater demand in Mexico for low-carbon building materials.

These numbers will continue to grow. Around the world, more than 1 billion people live in inadequate housing. Increasing urbanization means that the majority of construction in coming decades will be mainly concentrated in the global south. Scaling up low-carbon cement technologies there will be critical to meeting demand. Already, according to the new IFC report, green hydrogen technology and carbon capture offer promising solutions for decarbonization in the cement industry.

“There is an estimated demand for more than 9 million homes in Mexico, which means a great opportunity for the entire industry to incorporate innovative construction systems and increasingly use low-carbon construction materials.”

Lowering the carbon footprint of a centuries-old material

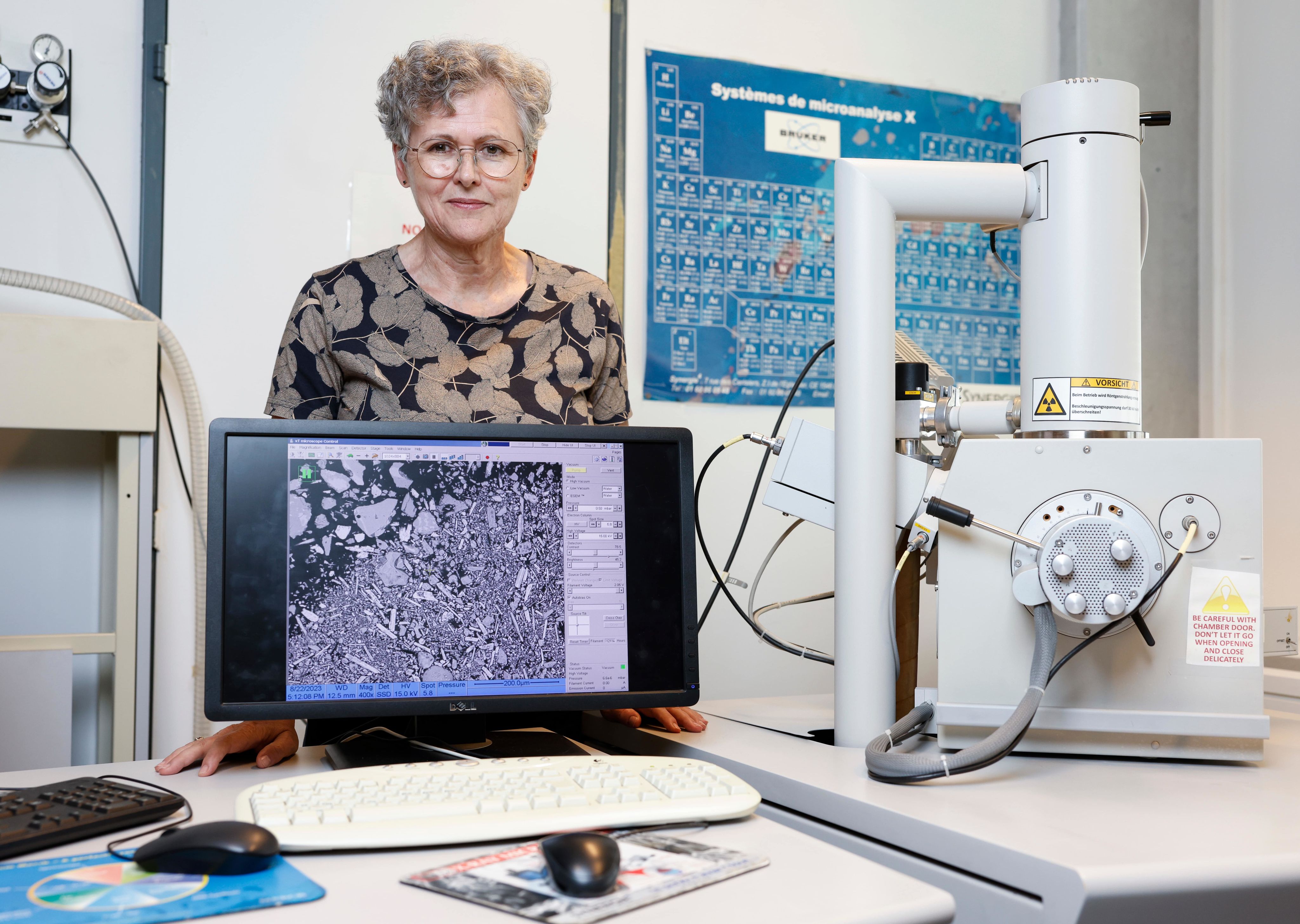

In a laboratory at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland, scientists have perfected a low-carbon cement that is already in production in plants across the world, including in more than 10 locations in Africa. The invention, called LC3 cement, is the brainchild of Karen Scrivener, a British material chemist who has been tweaking the chemistry of this centuries-old material for decades.

When making traditional cement, limestone is heated to very high temperatures in a carbon-intensive machine called a kiln which produces clinker. Producing clinker releases CO2 in two ways: by burning fossil fuels and by the chemical reaction when the limestone is broken down. LC3 cement replaces half of the clinker with a combination of calcined clay and ground limestone. The clay is calcined at much lower temperatures, around 800 C, which reduces emissions and uses less energy, making the process less expensive.

As an example, Scrivener suggests that if the 768-meter-long Madre Laura Bridge in Colombia were built with LC3 cement rather than traditional cement, it would have saved more than 9,000 tons of CO2. That’s the equivalent, she says, of flying 15,500 passengers across the United States from San Francisco to New York City.

“Concrete is the second most used substance on earth, after water. We can’t do without it but we can significantly reduce its carbon footprint.”

With 40 percent lower emissions than traditional cement, LC3 can also be made using impure clay, a practical attraction for many emerging markets with abundant lower-purity clay deposits. With full-scale trials already completed in India and Cuba, and calcining plants already operational in Africa and India, LC3 is already making inroads in multiple markets.

“LC3 is already there. We want it to go faster but there is no barrier in terms of scale,” says Scrivener. “We can do this across the vast majority of the world and you can install [calcining plants] in one to two years. This is what’s important because we need to make CO2 savings now. We can’t wait for some miracle solution that may come along in 50 years.”

Karen Scrivener, inventor of LC3, a low-carbon cement.

Karen Scrivener, inventor of LC3, a low-carbon cement.

If you build it, they will come

But since sustainable finance markets are less developed in emerging markets, questions remain. An especially pressing issue is how to achieve a substantial reduction in emissions from the construction sector. Already in Mexico, savvy financial institutions are developing innovative products to capitalize on burgeoning demand.

In July, Santander, Mexico’s second-largest bank, unveiled a new green mortgage product in alliance with IFC. The offering targets homeowners like Lōpez and Suarez to encourage them to purchase affordable low-carbon homes. The product offers mortgages as low as $10,000 at a rate of 8.85 percent – the lowest rate available anywhere in Mexico – on the condition that the home is EDGE Advanced certified. In October, another banking giant in Mexico, HSBC, followed suit with a similar green mortgage product. Since then, Scotiabank, Mifel and Banorte have introduced similar initiatives.

Santander will also support property developers by offering access to sustainable financing, promoting the transition towards a green economy for construction companies in Mexico.

Antonio Artigues Fiol, Santander’s Executive Director of Personal Banking

Antonio Artigues Fiol, Santander’s Executive Director of Personal Banking

“Demand [for green housing] is now growing to the point that the supply chain is looking for ways to solve. Our initiative responds precisely to merge these two sides, between supply and demand, so that clients who are looking for this type of housing can access the best market conditions and builders can be incentivized to build that type of housing knowing that there is also a growing market.”

Back at Real Navarra, as rambunctious children return home to the development from a nearby school, Suarez reflects on how the new neighborhood has changed his life for the better.

His home’s green design elements have transformed his energy bills, lowering them enough to significantly improve his family’s quality of life.

“I use these savings to go for walks [with my family], to go to a restaurant, to visit the magical towns that we have nearby,” he says.

“I use these savings to go for walks [with my family], to go to a restaurant, to visit the magical towns that we have nearby.”

Alison Buckholtz, Sol de Maria Galvan, Angela Njeri Mureithi and Julia Schmalz contributed to this story.

Published in October 2023