Building Green in a “Code Red” Climate

Why investors, developers, and governments are adopting zero-carbon goals.

The need was obvious—grimly obvious, Kofi Essel-Appiah remembers.

As the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic bore down on Ghana, the number of sick people spiked. Overburdened treatment centers struggled to care for patients whose illness was still a mystery, and there was no relief in sight.

But one especially promising solution—designing and building an infectious disease hospital in Accra, the capital, in just a few months—seemed like “an outrageous idea,” even to the most committed financial backers.

Essel-Appiah, an architect, signed on as project manager and lead consultant anyway, pledging his services pro bono. He immediately started recruiting local industry professionals for the effort.

“When the pandemic started, we saw that every country had to solve the problem on its own,” he says. “We had to look inside ourselves and determine what we were capable of as a nation. We decided we had to develop a place that would contain the disease and help people get better.”

“We had to look inside ourselves and determine what we were capable of as a nation." —Kofi Essel-Appiah

There were practical design matters to consider, too. Essel-Appiah believed that his knowledge of green building practices would help keep the running cost manageable—ensuring the long-term success of hospital operations. “We had to ensure a low cost of cooling, no loss of energy, and good water-saving measures,” he remembers. The team settled quickly on a plan for a green building because “There’s a quicker payback, so it made economic sense.”

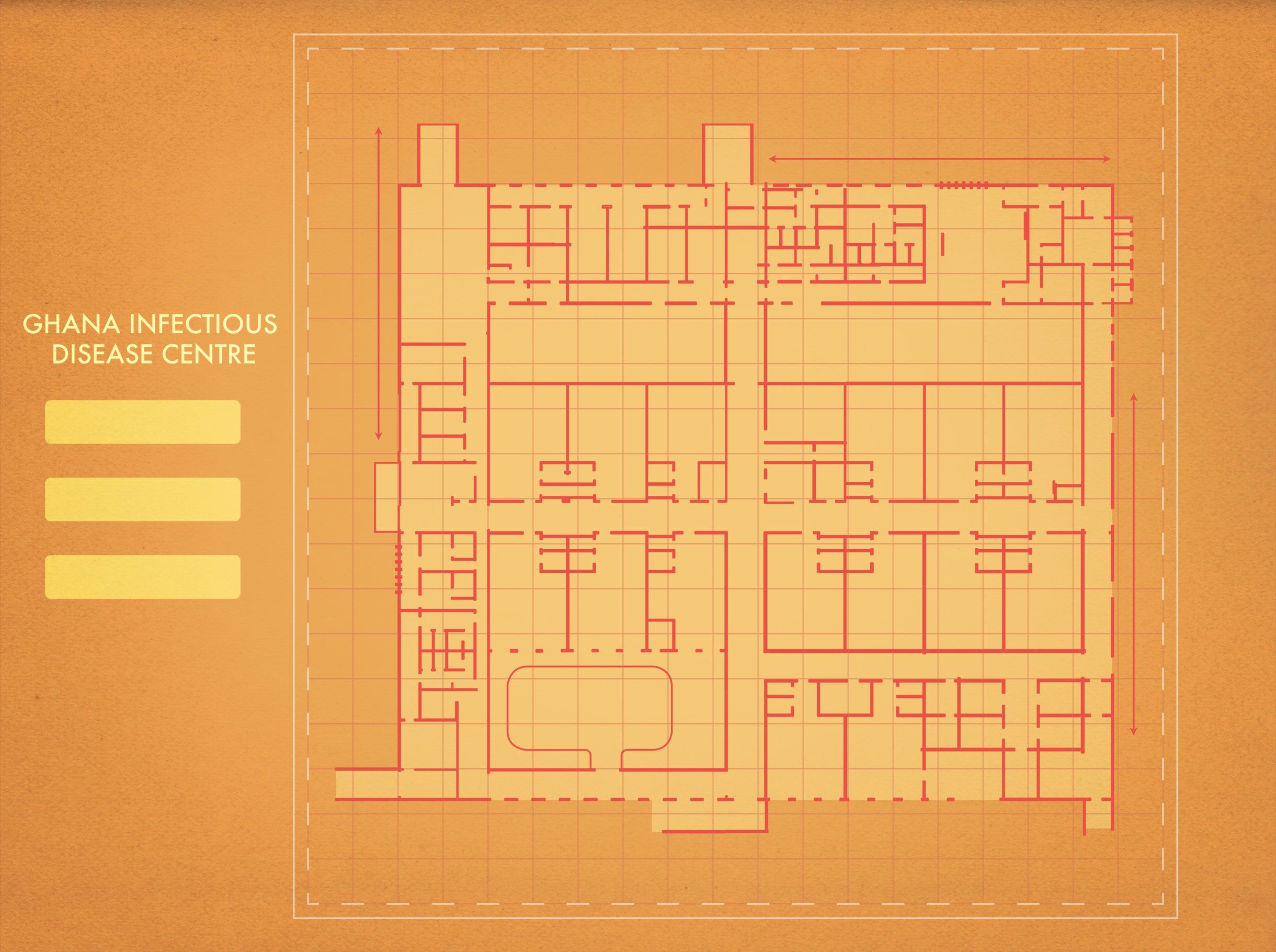

Then the “outrageous idea” took shape. Hundreds of professionals, consultants, and construction workers showed up around the clock to build the 100-bed Ghana Infectious Disease Center, the first of its kind in the country, in just under three months. All of the professionals, like Essel-Appiah, donated their time. The new building, supported by the Ghana COVID-19 Private Sector Fund, began treating patients in June of 2020 and is the country’s major referral point for COVID-19 patients who need intensive critical care.

Just over a year after opening, the running cost savings is 30 percent or more. That has caught the attention of Ghana’s Ministry of Health, which operates the hospital. “There is strong political interest in the potential of green buildings now,” Essel-Appiah says.

Cost-savings are part of the appeal. But Ghana’s newest green building is also the result of a worldwide, decades-long push to construct energy efficient building systems that prevent further global warming.

Decreasing emissions is key, as the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned in 2018, when it declared that greenhouse gas emissions must halve by 2030 and drop to net zero by 2050 to avoid the catastrophic impacts of climate change. Findings from the most recent United Nations report—which UN Secretary General António Guterres called “a code red for humanity”—suggest that aggressive emissions cuts that start immediately, and take place globally and across sectors, could limit the warming beyond 2050.

Zero-carbon building “is where everybody has to go eventually,” said Alex Buechi, a partner at Asia Green Real Estate, which provides investors access to sustainable residential and office investment opportunities in Asia. “[But] the speed of getting there varies from market to market.”

Why zero-carbon buildings matter

Zero-carbon buildings (also called “net-zero”) are usually defined as highly-efficient new or retrofitted structures that are fully powered from on- or off-site renewable energy sources like wind and solar. Zero-carbon buildings are super energy-efficient—Prashant Kapoor, Chief Industry Specialist for Green Buildings and Cities at IFC, calls them “bright green”—and have higher standards for energy efficiency than traditional green buildings. To be certified so the developer can qualify for incentives and benefits, they typically must show energy savings of more than 40 percent, compared to a traditional building. Buildings and homes are called “net zero-ready” when they are designed to be fully powered from on- or off-site renewable energy sources and offsets.

Zero-carbon buildings and the green building industry support the transition to clean energy while driving low-carbon economic growth, said Kapoor, who created IFC’s EDGE software and certification program to help developers, investors, and governments measure and communicate the value of green building projects. The green building sector represents an over $24 trillion investment opportunity across all emerging-market cities—especially in Asia, where over half the world’s population will reside by 2050.

Net-zero carbon emissions targets are gaining momentum around the world, according to research from Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Seventy percent of world emissions are either already covered by net-zero legislation, have net-zero emissions legislation under discussion, or occur where net-zero is the policy position of the government.

Architect Essel-Appiah and his team in Ghana have observed that political will has boosted plans for more green buildings. While the Ghana Infectious Disease Center continues to meet climate-related and cost-saving milestones, for example, government officials are looking into building additional green hospitals in the country, he says.

Photo by: Festus Jackson-Davis

Ghana’s National Building Code has integrated green building strategies and third-party certified standards like EDGE in a way that “can serve as a model for other emerging-market countries,” according to Dominique Paravicini, head of Economic Cooperation and Development for the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs SECO, a leading supporter of IFC’s Green Buildings Certification Program. The projects in Ghana are “critical” to SECO’s wider, ongoing effort to scale up construction of more resource-efficient buildings, he says.

Government reforms and policies that promote zero-carbon buildings and include incentives for meeting milestones “send a clear market signal” and influence the private sector’s decisions to build to higher standards, says Kapoor. Governments can “shift the market with their huge aggregate demand, which in turn can trigger the development of a pipeline of green buildings and related products."

Green buildings across the globe

In Colombia, a combination of government incentives, partnerships, and technical assistance to developers, alongside innovative green finance offerings, has helped transform the nation’s green housing market in just a few years.

First, in 2015, the national government enacted a Green Building Code, and introduced tax incentives for technical solutions such as insulation and energy-efficient air conditioning systems. Two years later, the commercial banks Bancolombia and Davivienda launched green investment programs for new housing, and green building strategies gained further momentum. Now, five banks are offering green mortgages. Throughout, Colombia’s Chamber of Construction (CAMACOL), IFC’s local partner, has promoted the benefits of building green and helped private sector developers become EDGE-certified.

Colombia’s progress serves as a model for the region: As of September 2021, the nation had 5.9 million square meters of certified green space. Close to 73,000 green homes have been EDGE certified, two-thirds of which qualify as affordable housing. IFC estimates that about 20 percent of new builds were certified by July 2021.

Green building codes in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia, and in Bandung, the nation’s fourth-largest city, reduce energy consumption by setting energy and water-efficiency requirements in commercial as well as residential buildings. These green building initiatives will potentially help save 1.3 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions per year, cut 1.7 million megawatt-hours of energy use, and save almost $153 million per year, according to an IFC analysis. As of late 2019, approximately 8,500 buildings in Jakarta and Bandung had complied with the green building code.

In the City of Mandaluyong in metropolitan Manila, “The key to market transformation is through each local government unit adopting green building regulations,” says Armando Comandao, Department Head of Mandaluyong City Planning and Development Office. “Green building regulations play a crucial role in driving climate-smart real estate investments into the city, which is important especially in the time of climate change, the pandemic, and economic recovery.”

Mandaluyong City’s green buildings ordinance informed the development of the Philippine Green Building Code. The potential of the nationwide code to bring down costs is significant because the Philippines has one of the most expensive electricity rates in the region, which puts pressure on owners and renters of both commercial and residential buildings.

How green housing can improve lives

Lydwina Sicad remembers that pressure. The 62-year-old single mother of four raised her children in metropolitan Manila, where high utilities costs made it difficult to save money. Two years ago, her children surprised her with a gift: a net-zero ready home in Via Verde, about 60 kilometers from Manila, built by Imperial Homes Corporation.

The cost savings made an immediate impact on her household budget. “In Manila I would usually pay around Php 3,000 (about $60) for our monthly electricity bill. Because of solar power and the energy-efficient features of my home, I pay only around P600 (about $12) per month,” she says. She set aside money to start a business, and now sells rice cakes and Filipino delicacies such as leche flan, halaya, and ube flan in the village. The benefits of her new earning power have rippled through the community: She invites neighbors who can’t afford a fast Internet connection to use hers when they need it for their own work.

The potential to drive down utilities costs and improve the quality of life for low-income people in Cape Town, South Africa motivated Renier Erasmus, the founder and CEO of Madulammoho Housing Association, to invest in green building elements. At Belhar Gardens, the first EDGE-certified social housing project in South Africa, features like the window-to-wall ratio have helped residents save on energy usage.

That’s allowed Velia Ketame and her husband, Marlon, to save about 1,000 rand (about $63) every month since they moved there. “Now I can go extra with the food, I can buy extra clothes, extra shoes” for the family, she said last year. “There’s no more like, ‘I don’t have now, and I can’t do it now.’”

In Kenya, where more than 60 percent of urban households live in slums, green housing is helping to close the housing gap. With demand for housing at an all-time high and a cumulative housing deficit of 2 million units, the government announced a plan last year to provide developers with free land to build affordable housing projects that meet higher standards for green building. The goal: 500,000 homes that are affordable to buy and to live in by the end of 2022.

Similar projects to construct green housing in emerging markets are supported by the U.K.-IFC Market Accelerator for Green Construction Program, a partnership between IFC and the U.K. Government. The program aims to catalyze financing for certified green construction and green mortgages to mobilize investments that help tackle climate change.

New math for new solutions

The cost of constructing green buildings, whether residential or commercial, is often balanced against long-term savings for the owners. For housing, even a modest increase in the cost of each home’s construction could deliver significant energy savings throughout its entire life cycle, says Ran Boydell, a visiting lecturer in Sustainable Development at Scotland’s Heriot-Watt University.

“Housing stock is a long-lasting part of a society’s infrastructure, of value to people now and in future generations,” he points out.

Buildings designed with the EDGE tool generally cost less than 3 percent more than those constructed without requirements for water and energy efficiency. Research indicates that green buildings like these are a higher-value, lower-risk asset than standard structures: they can decrease operational costs by up to 37 percent, achieve higher sale premiums of up to 31 percent and faster sale times, have up to 23 percent higher occupancy rates, and earn higher rental income of up to 8 percent. Results from IFC’s work in green building codes through early 2021 shows that a green code covering the biggest buildings in Jakarta is saving at least $150 million a year in operating costs.

Employment opportunities and economic resilience also factor into the green building equation. The process of decarbonizing buildings generates local jobs as well as a demand for materials and services from local businesses, according to findings from C40, a network of the world’s megacities and mayors committed to addressing climate change.

Among the series of climate actions with the best record of job creation potential for local people, “retrofitting buildings, and new energy efficiency construction, was the highest out of all of the climate actions,” says Cassie Sutherland, C40’s program director for energy and buildings. “Building, retrofitting, and upgrading building stock is not going to be done overnight, so cities and their residents can benefit from the jobs this will deliver long-term.”

Photo courtesy: IDC

Investors speak up

An environmentally conscious approach to building is appealing to more and more investors, according to Günther Thallinger, Member of the Board of Management of Allianz SE and Chair of the United Nations-convened Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance. There’s growing agreement that “responsible investment and responsible building go hand in hand,” he says.

The Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance consists of more than 40 institutional investors committed to transitioning their investment portfolios to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. This joint effort by the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative and the Principles for Responsible Investment was founded by investors that together represent $6.6 trillion assets under management.

Investors’ motivations vary, according to Buechi, from Asia Green Real Estate. “Private investors want to see their investments in green buildings result in a higher-quality building with higher cash flows and higher capital gains,” he says, while pension funds are particularly interested in long term stability.

Green buildings account for more than 80 percent of the $29.4 trillion in investment opportunities that will open up in emerging-market cities by 2030. Building retrofits represent a $1.1 trillion investment opportunity, and could create 25 million new jobs globally by 2030, according to an IFC analysis. Policies to stimulate green construction could create another $25 trillion in investments in the same time span.

“For the nation and for humanity”

Despite introducing profound challenges to businesses everywhere, COVID-19 has led to a surge in e-commerce and follow-on growth in the warehouse sector, as McKinsey research shows. In India, online shopping has led to investment growth in the warehousing and logistics sectors so notable that it may experience the “fastest recovery” of any sector in the nation, property consultancy firm Savills India has reported.

This has heightened the appeal of the green warehouses owned by IndoSpace because they reduce the harm caused to the environment and provide certain cost benefits to the client, according to Rajesh Jaggi, Vice Chairman of Real Estate at The Everstone Group. He said that 14 million square feet of buildings by IndoSpace are certified by EDGE, of which more than 50 percent have the Advanced EDGE Certification. IndoSpace aims to get the entire portfolio certified by the end of fiscal year 2022.

At IndoSpace Vallam Industrial Park near Chennai, tenants of the EDGE-certified building operate in a resource-efficient environment, allowing them to reduce their utility bills and channel more funds into their businesses. These green features are expected to reduce the utility costs of the building by more than $4,000, allowing tenants to pay nearly half the amount it would cost to operate in a traditional warehouse.

Demand from online retailers is also helping to boost green warehouse growth in Romania. Jeroen Biermans, responsible for building resource-efficient warehouses and commercial properties across Romania for logistics real estate company WDP, believes that the explosion of online shopping brought on by COVID-19 means that green logistics buildings for e-commerce could be one of the most lucrative businesses to emerge from the pandemic.

Biermans says that the Stefanestii de Jos warehouse in Bucharest, one of the buildings he oversees, is among the greenest buildings in Europe. It uses at least 20 percent less energy and water than other buildings, makes use of efficient, sustainable lighting, and takes care of waste reduction. In his view, such buildings can “promote sustainability across the supply chain in order to support the real economy.”

Photo courtesy: WDP

Economics are also important to Essel-Appiah, the architect behind the Ghana Infectious Disease Center. But the building represents something greater than the sum of its operational cost savings. It’s a cultural milestone that shows what Ghanaians can achieve when they unite to solve a problem.

“We had to dig deep,” he says. “As a country, we looked inside ourselves and built something sustainable for the nation and for humanity, and I couldn’t be prouder.”

Angelo Tan and Manuela deSouza contributed to this story.

Concept and layout by Rayna Zhang.

Illustration at top based on a photo by Russel Eni/Insel Ghana.

Published September 2021

To join the conversation about green buildings: #ClimateActionWBG.

Developers interested in exploring green building certification through IFC may do so by visiting EDGE Buildings online, where they can begin the certification process using the free app.

Read more about business solutions to climate change