Meet the Women

Sowing Senegal's Future

Women in Senegal are reinventing rice farming techniques to confront climate change and ensure food security. Through entrepreneurship and activism, they are reinventing themselves, too.

As Senegalese caterer Aminata Niang dips her long ladle into a bowl of broth and pours it onto a plate piled high with ceebu jën —the national dish of seasoned fish and vegetables served over steamed rice—she glances up and gestures guests to the table.

Even though she has been preparing this dish, known in French as thiebou dienne, since she was a child in her mother’s kitchen, this meal is different. She made it with local rice grown near her home in Saint-Louis rather than with imported rice, which she typically uses. The local rice, known as “broken rice” because of its short, fractured grain, is becoming more popular and is requested with greater frequency throughout Senegal, she explains.

Thiebou dienne, often made with rice grown in the Senegal River Valley, was named a “culinary art of Senegal” by UNESCO in 2021. The citation called the dish "an affirmation of Senegalese identity."

Thiebou dienne, often made with rice grown in the Senegal River Valley, was named a “culinary art of Senegal” by UNESCO in 2021. The citation called the dish "an affirmation of Senegalese identity."

It's not just a question of taste: national pride plays a role in the choice, too. That’s because home-grown rice is a key ingredient in Senegal’s recipe for self-sufficiency.

“People in Senegal want to eat something that’s grown in Senegal, so we don’t have to depend on other countries to keep our people fed,” says Korka Diaw, who operates a 150-hectare (370 acres) rice farm in the Senegal River Valley, 320 kilometers (200 miles) north of Dakar. She’s referring to the fact that Senegal imports more than half of its rice from other countries. “But it’s important for a lot of other reasons as well,” she adds.

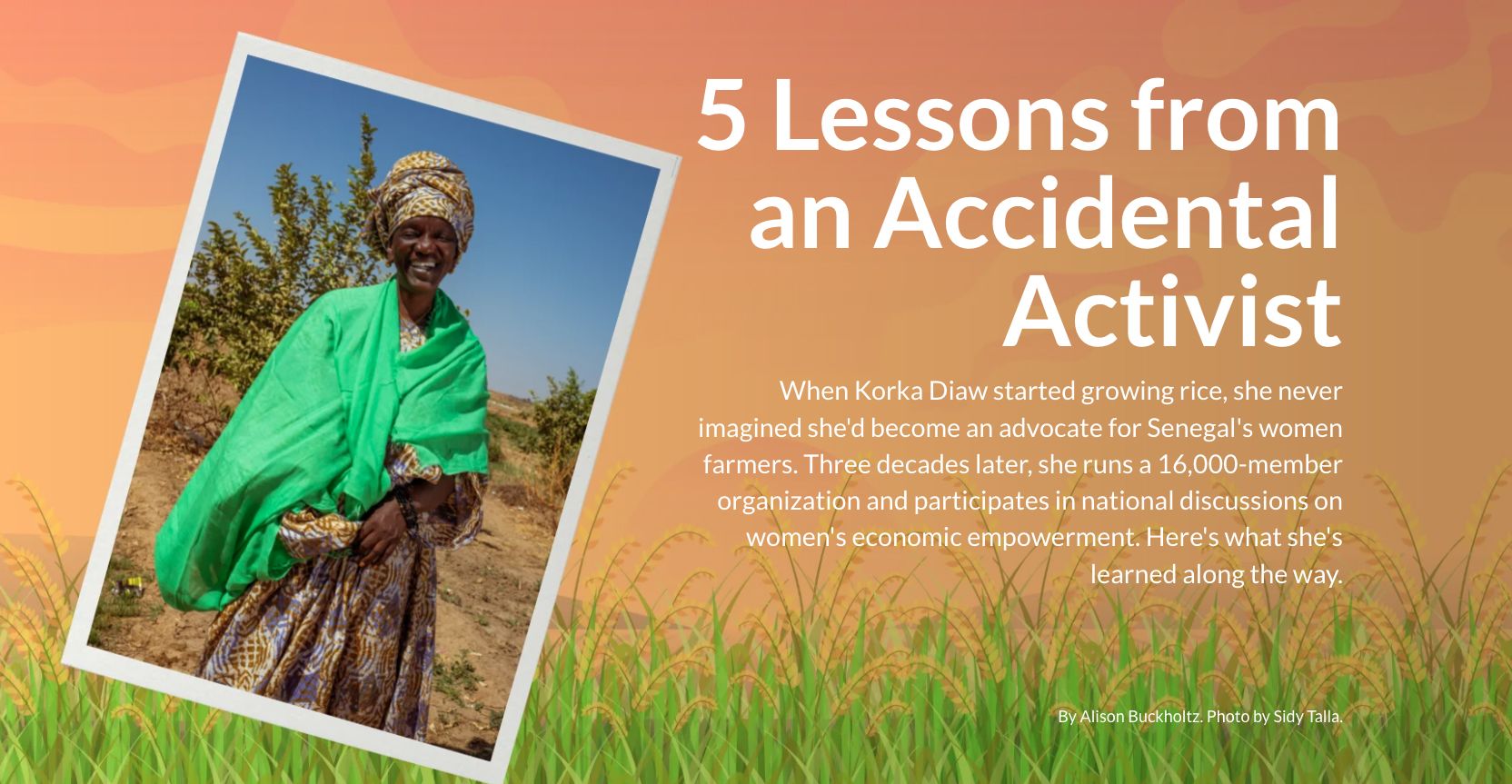

Korka Diaw began growing rice in 1991 and has become a nationwide advocate on behalf of Senegal's women farmers, whose access to land and finance is limited. Click here for her "5 Tips from an Accidental Activist."

Korka Diaw began growing rice in 1991 and has become a nationwide advocate on behalf of Senegal's women farmers, whose access to land and finance is limited. Click here for her "5 Tips from an Accidental Activist."

Many others agree. The availability of home-grown rice is critical to food security in Senegal and sub-Saharan Africa, according to the World Bank and International Finance Corporation (IFC), which have for decades supported national and regional strategies to strengthen agriculture production. Climate change—together with the lingering effects of the pandemic and the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—has created an acute vulnerability to price volatility and shortages worldwide, as World Bank research notes.

But the solution isn’t as simple as ramping up Senegal's domestic production to meet demand. High temperatures and erratic rainfall, attributed to climate change, require heat-resistant seed varieties, flexible planting schedules, adaptive farming practices, and even new machinery, says Diaw.

The multiple challenges confronting Senegal are shared by many other African countries. What makes Senegal’s approach to the rice crisis unique is the part women play in supporting the country’s National Rice Self-Sufficiency Program, which aims for rice self-sufficiency by 2030. “Rice is a priority sector for Senegal,” says Waly Diouf, the program coordinator. “Women play a key role in the rice-growing sector, both in terms of production and processing….[and] we want to help them be as effective as they can.”

To meet national needs, today’s women rice farmers require access to finance, training, and professional resources, according to Diaw. “Our ancestors and our parents farmed for subsistence,” she says. “Now, farming is a revenue-earner and we’re part of the agribusiness industry. We’re feeding the nation, providing jobs and education, building processing facilities, and training the next generation of young women farmers, all in a period of climate uncertainty. It’s a huge responsibility, and everyone has a role to play.”

An appetite for finance

Empowering women rice farmers with access to finance and training is key to strengthening Senegal’s food security, according to Sérgio Pimenta, IFC Regional Vice President for Africa. "Agriculture is Senegal's main driver of economic growth, and IFC is committed to supporting the agriculture and rice value chains in Senegal."

Much of Senegal’s domestic rice is produced in the Senegal River Valley, where cousins Ndobou Sene Fall and Aby Diop cultivate rice and other crops on a rust-red, 10-hectare field in the rural village of Mboundoum Barrage. As in the other rice-growing areas of Senegal, crops are planted in carefully irrigated rows of soil rather than in watery rice paddies.

Cousins Ndobou Sene Fall and Aby Diop grow rice and other crops in the rural village of Mboundoum Barrage in the Senegal River Valley. Women farmers produce more than 80 percent of crops in Senegal, especially food crops.

"Selling rice within Senegal is important to me, and demand is increasing, but now, because of climate change, we have a hard time supplying it," Fall says.

Ndobou Sene Fall’s son, El Hadj Dienou Faye, is helping modernize the family's farming techniques. He uses GPS to measure the fields, a time-saving move that has introduced precision into a generations-old farming process.

“We used to mark lengths of the field with string, cut the string, then bring it home to measure,” he says. “GPS makes this much easier.”

The cousins grew up farming this land to provide food for their large, extended family. As adults, they began selling their harvests in large markets and hired additional workers to help. The biggest change, as Fall explains, has been the weather.

“Farming is much harder than it was before due to climate change,” she says. “We can no longer sow and reap as in the past. The seasons are disrupted. We are forced to change the timing, or the crops will not ripen.” Because the rains come earlier and are heavier, the women continually adjust their plans: instead of planting in March, they must plant 10 to 20 days before that, guessing at the best date and hoping the rainy season doesn’t arrive unexpectedly and destroy everything. Rainfall is the key climatic determinant of food production, according to the World Food Programme.

Accommodating these changes makes farming “much more work than before,” according to Fall. “Selling rice within Senegal is important to me, and demand is increasing, but now, because of climate change, we have a hard time supplying it. For everything you do [to adapt to climate change] you need money. Funding is our major problem.”

Pursuing gender equality

Financing from Baobab Group, an IFC client that provides financial services across West Africa, has helped their family adapt its farming techniques to climate change. In the past several years, Fall has received five loans ranging in size from FCFA 400,000 (about $667) to FCFA 6 million (about $10,000). Her cousin, who farms on two hectares adjacent to Fall’s land, has also received loans from Baobab.

The loans have allowed them to work around the problems caused by heat and unpredictable rainfall by managing pests that plague the harvest and purchasing seeds that withstand high temperatures. Rice breeders are creating new varieties that can endure changes in climate, and when smallholder families like hers can access these seeds, it benefits everyone, she says.

IFC's financing for Baobab is through IFC’s Base of the Pyramid Platform (BOP), which helps financial services providers deliver critical funding to small and informal businesses, and low-income households. The BOP is backed by pooled first-loss guarantees and local currency financing from the International Development Association's Private Sector Window.

Opportunities for private sector development are also expected to result from the just-launched Senegal River Valley Development and Resilience Project, a joint World Bank and IFC initiative in Senegal and Mauritania, which lies on the other side of the Senegal River. The World Bank's $195 million contribution will help address the many climate challenges affecting communities on both sides of the Valley and hindering the region’s socioeconomic development.

IFC and the World Bank are engaged in several long-term projects with the Government of Senegal to ensure that investments in the agriculture and food sector match the urgency of the climate crisis while reducing the gender divide in the agricultural sector.

Baobab Group has made it a priority to help Senegal’s women rice farmers increase their productivity, says Baobab Senegal Deputy CEO Serigne Bamba Mbacke Diop. The volume of loans disbursed to women farmers increased by 54 percent between 2021 and 2023, and the company's training and support programs are geared "to strengthen [women farmers'] financial autonomy." Targeted initiatives include training to improve environmentally-friendly production techniques; access to insurance products adapted to the different types of crops and climatic realities; and advocacy to facilitate their access to land, in addition to facilitating access to finance.

Mariama Sane, Baobab Group's client services officer in Saint-Louis, says that loans to women farmers in the Senegal River Valley range from CFA 100,000 (about $165) to CFA 100,000,000 (about $165,000). The African Development Bank estimates a $15.6 billion financing gap for African women in agriculture.

Mariama Sane, Baobab Group's client services officer in Saint-Louis, says that loans to women farmers in the Senegal River Valley range from CFA 100,000 (about $165) to CFA 100,000,000 (about $165,000). The African Development Bank estimates a $15.6 billion financing gap for African women in agriculture.

IFC and IMF research shows that most of the potential for creating jobs and revenue among Senegalese women lies with the private sector. While male entrepreneurs in Senegal face significant constraints accessing finance, micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises led by women or based in rural areas “have even lower access.”

This is because “access to land and access to finance are two of the most significant structural barriers for women farmers,” says Elena Ruiz Abril, UN Women’s Regional Policy Advisor for Women’s Economic Empowerment for West and Central Africa. Limited access to financial resources results in reduced productivity. For instance, without the means to acquire equipment or rent tractors, women often find themselves confined to subsistence farming.

The government is also stepping in to facilitate women’s use of modern equipment. New government rules enacted in 2015 stipulate that when equipment is acquired by the government, particularly within the Ministry of Agriculture, 30 percent of all the equipment is automatically reserved for women, according to Waly Diouf, of the rice self-sufficiency agency. By facilitating access to modern equipment, “we are helping women farmers avoid crop losses, have time for other economic activities, and take care of themselves,” he says.

"Everyone is equal before the land. But it doesn't always work out that way in practice." —Korka Diaw

Cultivating sustainability

In addition to financing, Fall and Aby Diop’s biggest priority is seeking out information and training on farming practices and inputs (such as seeds and fertilizers) adapted to climate change. Korka Diaw remembers how difficult it was to find such resources when she started farming. “Everyone is equal before the land,” Diaw says, “but it doesn’t always work out that way in practice.”

Because women farmers are traditionally overlooked and underfunded in Senegal, they must turn to each other, Diaw believes. That’s why she founded REFAN, a 10-year-old nationwide network that helps women farmers access financing, training in techniques to adapt to climate change, and the latest information on farming developments. (REFAN is the French acronym for Network of Women Farmers in the North of Senegal. Despite the name, it includes women farmers from across the country, and about 30 percent of membership is comprised of small traders and fisherfolk.)

REFAN offers its 16,000 members a wide range of services, including training and information on agricultural techniques, insurance, and business development. The group also provides rural women information on health care, and is involved in shaping women's access to medical resources.

“There was no organization like REFAN when I started farming,” Diaw says, “but I want to make sure other women have an easier time than I did.”

This rice sack is labeled “produit dans la vallée du fleuve Senegal” because the farm lies in the Senegal River Valley. Increasing the production of home-grown rice is a critical step toward decreasing food imports. The African Development Bank calls rice self-sufficiency a "national security issue."

"From 2014 to today, Senegal's rice production has increased every year," says Waly Diouf. "Senegal is on the right track to achieving rice self-sufficiency."

Research shows that information-sharing and training that improves women farmers’ knowledge of new technologies is a major factor powering the shift to sustainable agriculture. One of Diaw’s primary goals for REFAN is to provide such resources. “There was no organization like REFAN when I started farming,” Diaw says, “but I want to make sure other women have an easier time than I did.”

She remembers her own inauspicious start in 1991, when she launched with capital of FCFA 10,000 (about $15): “I was a trader, but I looked around and saw the opportunities for growing rice. I borrowed an acre and produced food for my family. I had to heavily finance the land for water development and there was no one to teach me.”

In Diaw’s case, as she recounts, “I have a quality no one counted on: Endurance.” With financial support and training from development agencies and the private sector, Diaw continued to grow her business, purchasing successively larger farms. Her crew of 40 employees now cultivates 150 hectares of rice and 20 hectares of vegetables and fruits. Her company, Korka Rice, handles the value chain from start to finish, including production, harvesting, processing, warehousing, and marketing. Technology has been important to her farm’s expansion since the impact of climate change means that “we don’t know what to expect,” Diaw says. We’re sowing in uncertainty.”

Click here to read more about what Korka Diaw has learned in 30 years of activism.

Click here to read more about what Korka Diaw has learned in 30 years of activism.

Amid this uncertainty, REFAN creates better conditions for its 16,000 members by negotiating with manufacturers to buy high-quality seeds and other inputs in bulk; promoting financial literacy; and offering training and information on agricultural techniques, technology, insurance, and business development. These efforts are supported by AGRIFED, UN Women’s flagship program on women’s economic empowerment through climate-resilient agriculture.

Fall and Diop, who are both members of REFAN, are considering its training sessions on the use of drones. “We welcome anything that can advance our farming efforts,” Fall says, noting that self-sufficiency is not just a national goal, but a personal aspiration as well.

To that end, Fall knows exactly what she would do with more financing and support. Her first move would be to purchase her land as well as the necessary operating machinery, instead of renting it by the hour, which limits her productivity.

“I want to be able to leave this to my kids,” she says, surveying long rows of seedlings that seem to reach the horizon. “That’s what I want. To pass along to my children something of value.”