Expanding Opportunities in Madagascar, One Microloan at a Time

How microcredit improves livelihoods for entrepreneurs and their families

Located off the southeast coast of Africa, Madagascar is home to more than 30 million people and an abundance of wildlife, most of which is found nowhere else on earth.

At the heart of the high plateaus of Madagascar, the capital Antananarivo—or Tana to those who call it home—is a bustling city surrounded by the 12 sacred hills of Imerina and embodies the country's vitality and contrasts.

The surrounding highlands are the breadbasket of the country, with market gardens, rice fields, and small livestock farms punctuating the countryside. But there is more to the region than just agriculture. Ancestral traditions paved the way for a robust craft industry, and many people from Tana and the region make their living from wood and aluminum work, raffia weaving, and embroidery.

Madagascar is rich in natural resources, yet it faces a history of uneven economic growth and persistent poverty, with over 80 percent of the population living on $2.15 per day. Financing remains hard to come by, limiting the opportunities for small businesses and the people who run them.

This is where microcredit comes in, offering entrepreneurs with little to no collateral or banking history access to the financing they need to start or expand income-generating activities, improving the quality of life for them and their families.

In 2021, IFC launched the Base of the Pyramid Platform, supported by the blended finance and local currency facilities of the International Development Association’s Private Sector Window (IDA PSW), to help financial service providers deliver funding to small businesses, women entrepreneurs, and informal enterprises– underserved segments of the population crucial to boosting economic growth, creating jobs, and driving financial inclusion.

The use of local currency solutions is particularly impactful, as it protects borrowers by reducing the risk of default in the event of currency fluctuations and contributes to more sustainable development.

“MSMEs are the building blocks of emerging market economies,” said Kalina Miller, Regional Industry Manager for Southern Africa, IFC Financial Institutions Group. “We know the tremendous impact that access to high quality, convenient and affordable financial services can have on small businesses and the wellbeing of individuals, families, and communities.”

Under the Base of the Pyramid Platform, IFC has committed six projects in Madagascar since 2022, providing $49.5 million equivalent in local currency to support on-lending through UNICECAM, PAMF, ACEP Madagascar, Baobab Banque Madagascar and Société Générale Madagascar.

IFC’s collaboration with local financial institutions in Madagascar is expected to expand access to an additional 140,000 micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) by the end of 2027.

“MSMEs are the building blocks of emerging market economies. We know the tremendous impact that access to high quality, convenient and affordable financial services can have on small businesses and the wellbeing of individuals, families, and communities.”

Discover the inspiring journeys of three small business owners from the high plateaus

Patricia

“When we started out, we used to pay rent. Now we are owners, and we even rent out part of our property.”

Dawn has barely broken over Miandrarivo Ambanidia, a lively neighborhood perched high along the hairpin roadways of Antananarivo. Her husband and children are still asleep, but Patricia Rakotonirina is already stirring the pots on the stove. The little food stall on the street—or gargote as they are commonly known in Madagascar—opens every day at 6:00 a.m. She wakes up early to prepare the rice soup, samosas, meat, and potato balls that her neighbors and customers love so much.

By midday, the house she and her husband built behind the food stall at the end of a steep alley is filled with the sounds of their children playing, back from school, while Patricia continues her work. Her days are long, stretching late into the evening as she tends to the needs of her bustling food stall.

“I decided in 2010 to start this business because it was hard to find work. I used the little money I had to open the shop,” she said. Lacking sufficient funds to grow their business, Patricia and her husband turned to microcredit.

Like many small business owners in Madagascar, she found out about the credit institution by word of mouth. “I’ve been a PAMF customer since 2011. Completing my loan application was easy. The customer advisers explained things in stages,” because, as she admitted, “nobody understands everything the first time.”

The Première Agence de Microfinance (PAMF) has had a presence in Madagascar since 2006, with customers concentrated largely in the capital and in the north of the country. Its financial products are designed to address the specific needs of very small business owners. Women, with lower rates of non-performing loans, are seen as reliable borrowers and comprise more than half of PAMF’s 400,000 customers.

“PAMF’s vision of reducing poverty and including women in the financial system resonated with me,” says Tsirimpitiavana Rakotondrazafy, an SME loan officer at PAMF. Adding, “And it is one of Madagascar’s leading institutions.”

Tsirimpitiavana Rakotondrazafy

Tsirimpitiavana Rakotondrazafy

When it comes to granting loans, getting to know the customer, their business, assets, and personal experiences is key. Most customers of microfinance institutions (MFIs) cannot produce a bank statement or balance sheet. PAMF loan officers build relationships with their clients as a way to overcome this gap and determine their capacity and willingness to repay their loans.

In 2011, Patricia and her husband were granted an initial credit of 1 million ariary (or about $220). Now, they can borrow 3 million ariary (or about $660).

Their partnership with PAMF enabled them to expand their business (with plans to launch a new one) and improve their family’s well-being.

“When we began working with PAMF in 2011, we had only one person to help us. We didn’t have any children at the time; we were renting. It was credit that made it possible to hire a new employee. Now, we are owners, and we even rent out part of our property. We have two children, and we can afford to send them to school,” Patricia shares proudly.

“Thanks to the loan, we were able to hire two assistants. Our two children are in school. Everything is going well for us." -- Patricia Rakotonirina, pictured with one of her sons, in front of the house she and her husband built.

“Thanks to the loan, we were able to hire two assistants. Our two children are in school. Everything is going well for us." -- Patricia Rakotonirina, pictured with one of her sons, in front of the house she and her husband built.

Monique

“Our sales were taking off, but our finances were still on the ground. Friends of ours told us where we could get credit.”

Nestled amid lush hills and rice paddies about 70 km south of Antananarivo, Ambatolampy is known for its aluminum work, a legacy of centuries-old traditions. Here, the aluminum is melted then molded by hand to create utensils used in kitchens across Madagascar. Market stalls spill over with pans, pots, utensils, and tableware of various types. The city is home to many small-scale foundries, where the skills are passed down from generation to generation.

Monique Razaiarinoro runs one of these small factories. “We started this business about 35 years ago,” she told us. “We inherited it from our in-laws. My husband had been working in this field since he was a boy. One of our sons plans to take the baton. My husband oversees the workshop,” she added. “He's the one with all the experience in this trade. I manage the business. I take care of all the orders and our son deals with the sales and collecting the aluminum. We each have our responsibilities.”

The employees are working away in the workshop situated at the end of a clay-floored courtyard, strewn with metal objects of all sorts. To one side is the house, and on the other are the kitchen, the stable, and small sheds. Their movements are precise, repeated over and over—their technique unchanged over time.

The cooking pots are made from recycled aluminum bought from merchants or companies in Madagascar. Pipes, ball bearings, hub caps, and various other parts are first broken up and then melted in a brick oven in the middle of the courtyard. The red, viscous molten aluminum is then poured into a handmade mold filled with wet black sand found only in the rice paddies surrounding Ambatolampy. The workers tamp down the sand using their bare feet to ensure the sand mold holds its shape throughout. A few minutes later, after the aluminum solidifies, it is cooled and then removed from the mold. After sanding and polishing, the pots are ready for sale.

“We sell in Coum—the craft market in Tana. And we deliver orders in the countryside. Our customers are faithful customers. They give us a call and we deliver the products by van, truck, or bush taxi,” Monique explained before adding: “During peak season, we can hardly find time to sleep. There’s so much work to do.”

Over the years, the foundry grew and needed more financing. Today, it employs 12 workers—four women and eight men—and churns out up to 300 cooking pots per day. “Our sales were taking off, but our finances were still on the ground. Friends of ours told us where we could get a loan,” Monique explained. “A kilo of aluminum costs upwards of 20, 30 euros. It takes a lot of money to develop the business and increase production,” she added. “That’s why we reached out to ACEP.”

ACEP Madagascar serves micro and very small enterprises mainly in Antananarivo and the central regions. “When the economy is under pressure, we’re there to provide financing to small business owners,” says Managing Director of ACEP Madagascar, Mahefa Édouard Randriamiarisoa.

Mahefa Édouard Randriamiarisoa

Mahefa Édouard Randriamiarisoa

Small business owners, especially those living far out in rural areas have historically faced difficulties accessing financial services. To meet customers where they are, many MFIs receive requests through local branches across the country.

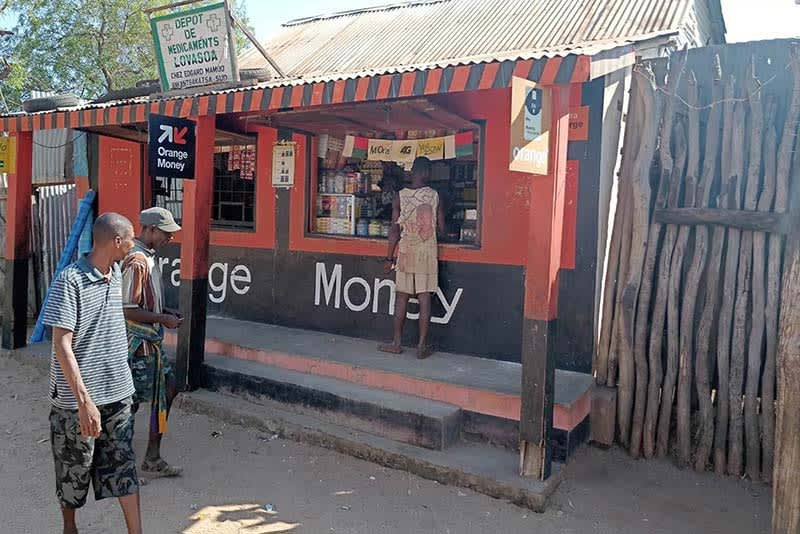

Thanks to the vast network of “Karibo” outlets (Karibo means “welcome” in Malagasy) built up across the country, microfinance customers can also carry out their financial transactions, such as depositing money or making their monthly payments, at nearby locations such as grocery stores, cash points, or markets, sparing them the trip to a physical bank branch.

A Karibo outlet in Ambatolampy facilitates financial transactions for small Malagasy entrepreneurs.

A Karibo outlet in Ambatolampy facilitates financial transactions for small Malagasy entrepreneurs.

As Monique relayed, “Applying for a loan from ACEP was easy, and talking to them was easy and a pleasant experience. Whether it was to get or repay a loan, it was easy.”

In addition to financial services and technical support, many MFI customers benefit from medical coverage for themselves and their families. This means better access to health care for Malagasy entrepreneurs and protection in the event of an accident or serious illness. “During the COVID-19 pandemic, three of us fell ill and had to be admitted to the hospital,” Monique said.

Although the loans are used mainly to purchase the raw materials, they also enabled Monique and her husband to hire more employees and purchase more delivery vehicles.

In addition to growing their business, Monique points out that the loans have enabled a different life for her family. “Our children have their own house now. We’re making progress in every area of our lives.”

“Our children have their own house now. We’re making progress in every area of our lives.” -- Monique Razaiarinoro, pictured with one of her sons who works alongside her.

“Our children have their own house now. We’re making progress in every area of our lives.” -- Monique Razaiarinoro, pictured with one of her sons who works alongside her.

Jacques

“After a while, I didn’t want to work for anyone anymore. I wanted to work for myself.”

Jacques Fidelis Randimbiarisoa, a craftsman living in the Avaradoha neighborhood in Antananarivo, dreamed of one day owning his own business. When he decided in 2013 to leave the province of Mahajanga in the west of Madagascar, and his job at the factory where they made wood model cars and boats, he had no home or workshop. But he and his wife were determined to try their luck in the capital so they could provide better opportunities for their children.

“Life in the countryside is hard, so I tried finding work in Antananarivo. After a while, I didn’t want to work for anyone anymore. I wanted to work for myself,” explains Jacques. “So, I built this little workshop.”

Jacques has always worked with wood, but it wasn’t until he came to live in Tana that he began making wall clocks. “I started out on a learning curve because it was all new to me. But it paid off. And now I have to employ people,” he told us.

Starting his own business was no easy task. Wood, his raw material, was a huge expense, especially for some of the rarer types that he works with. “Wood is expensive,” explains Jacques. These days, 1 million ariary (about $220) is not enough. You need 2 million ariary—not to mention having to buy more equipment to meet growing demand.”

In the beginning, Jacques and his wife managed to finance the business out of their own pockets. But news of their fine work soon spread, and little by little their products were being sold in every province of Madagascar. As their business grew, so too did the resources and capital required to run it. That’s when they decided to seek out a small loan.

According to Jacques, “We needed a regular supply of raw materials. A friend suggested we apply to ACEP for financing. He found their loans affordable and had a good experience doing business with them. So, we were able to finance our purchase of materials, such as the wood, glue, and the clock mechanisms. It was enough to finance that year’s output.”

The first loan Jacques Randimbiarisoa obtained was for 600,000 ariary (about $130). “Some agents came out to visit my workshop. They carefully observed what we were doing. And I managed to get the loan,” he explains.

As his business grew, Jacques was able to borrow larger and larger amounts. Today, he borrows 2.2 million ariary a year, or about $480—enough to keep his business running. “I don’t dare borrow a lot in one go,” he pointed out.

Many MFIs in Madagascar do more than just grant loans. They provide borrowers with financial literacy training to ensure they understand the terms of their loans, manage their loan repayments well, and sustain business growth. “ACEP was a real help,” explains Jacques, “because with each loan I was given more training. They taught us how to work out our cost price and how to increase our output.”

Today, Jacques and his wife own a flourishing business employing five people. The clocks and other wooden models that Jacques makes are sold across Madagascar in Malagasy craft shops. Their creations are also exported to Réunion, Mauritius, and mainland France.

With the financing they received, not only were Jacques and his wife able to expand their business and purchase delivery vehicles, but they were also able to buy a plot of land in Tana where they could build a workshop and their home. “My wife and I have been able to make concrete progress. We were able to build our home. We could send our children to school,” Jacques shares proudly. The eldest is now a civil engineer, while the younger two are still in school.

“My wife and I have been able to make concrete progress. We were able to build our home. We could send our children to school." -- Jacques Fidelis Randimbiarisoa, pictured with his wife.

“My wife and I have been able to make concrete progress. We were able to build our home. We could send our children to school." -- Jacques Fidelis Randimbiarisoa, pictured with his wife.

Published in December 2024

Further Reading