How Türkiye’s auto industry is driving economic growth

The sector has long been a key source of jobs and foreign currency. Now it must navigate the transition to the electric vehicle age.

By Andrew Raven

Six years ago, Turkish auto parts maker Martur Fompak was eyeing an expansion that would transform the company.

The firm, which makes seats, dashes and other interior components, wanted to ramp up its operations in Europe and forge connections with the continent’s biggest carmakers.

The expansion would cost a significant amount, so Martur Fompak turned to IFC.

The institution made a 30-million-euro equity investment in the company, providing not only capital but also the cachet that comes with the backing of a respected international investor, says Yalçın Türker, a member of the company’s executive board.

The partnership would help propel Martur Fompak’s European growth and today it has contracts with a who’s-who of the auto world, including Renault, Stellantis, Ford, Volkswagen and Toyota.

“It supported the future development of the company," says Türker. “Without IFC, we might not have been as financially strong when making decisions.”

IFC’s partnership with Martur Fompak is part of a nearly two-decade-long effort to support the growth of Türkiye’s automotive industry, which employs more than 500,000 people and is a key source of foreign exchange for a country battling a currency crisis.

Since 2005, IFC has worked closely with both local auto parts suppliers and major automakers based in Türkiye, helping them compete in one of the world’s toughest industries. Now, IFC is focused on helping the sector, especially local players, contend with what experts say is an inevitable shift towards electric vehicles.

“Türkiye isn’t endowed with natural resources, so to drive economic growth, it must excel at export-oriented manufacturing,” said Arnaud Dupoizat, IFC’s country manager for Türkiye. Speaking about the shift to electric vehicles he said: “So far, the auto industry has been a star, but electrification is changing the industry quickly and Turkish manufacturers will need to adapt.”

Türkiye has one of the largest automotive industries of any emerging-market economy, producing 1.3 million vehicles in 2021, according to government data. That total ranks 13th globally.

Since 2000, global brands, from Italian tire manufacturer Pirelli to South Korean auto giant Hyundai, have invested $16 billion in the country, feeding the growth of a network of local parts suppliers, like Martur.

A key part of IFC’s work is helping those suppliers extend their geographic footprints and weave themselves into global supply chains by striking deals with international carmakers.

Along with the partnership with Martur, IFC in 2021 invested in CY Vision, which builds heads-up displays, systems that cast information, like speed and driving directions, onto a car’s windshield. Earlier this year, IFC invested $110 million in Kordsa, which makes high-strength fibres used in tires. IFC also provided axle maker Ege Endüstri with a 40-million-euro loan, helping the firm build a modern, energy-efficient factory in Türkiye’s third-largest city, Izmir.

Breaking into global value chains is key for Turkish auto parts suppliers, said Dupoizat. It can create durable firm-to-firm relationships and allow local companies to hyperspecialize, bolstering productivity and revenues. A 2020 World Bank Group report found that in developing countries, these types of close business ties can help raise incomes and counter poverty much more effectively than traditional trading relationships.

As successful as Türkiye’s auto industry has been, the rise of electric vehicles is presenting new challanges. The number of passenger electric vehicles on the world’s roads is expected to increase 35-fold within the decade, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, a consultancy. Europe, where most Turkish-made vehicles end up, has announced plans to ban all sales of new gas-powered vehicles by 2035.

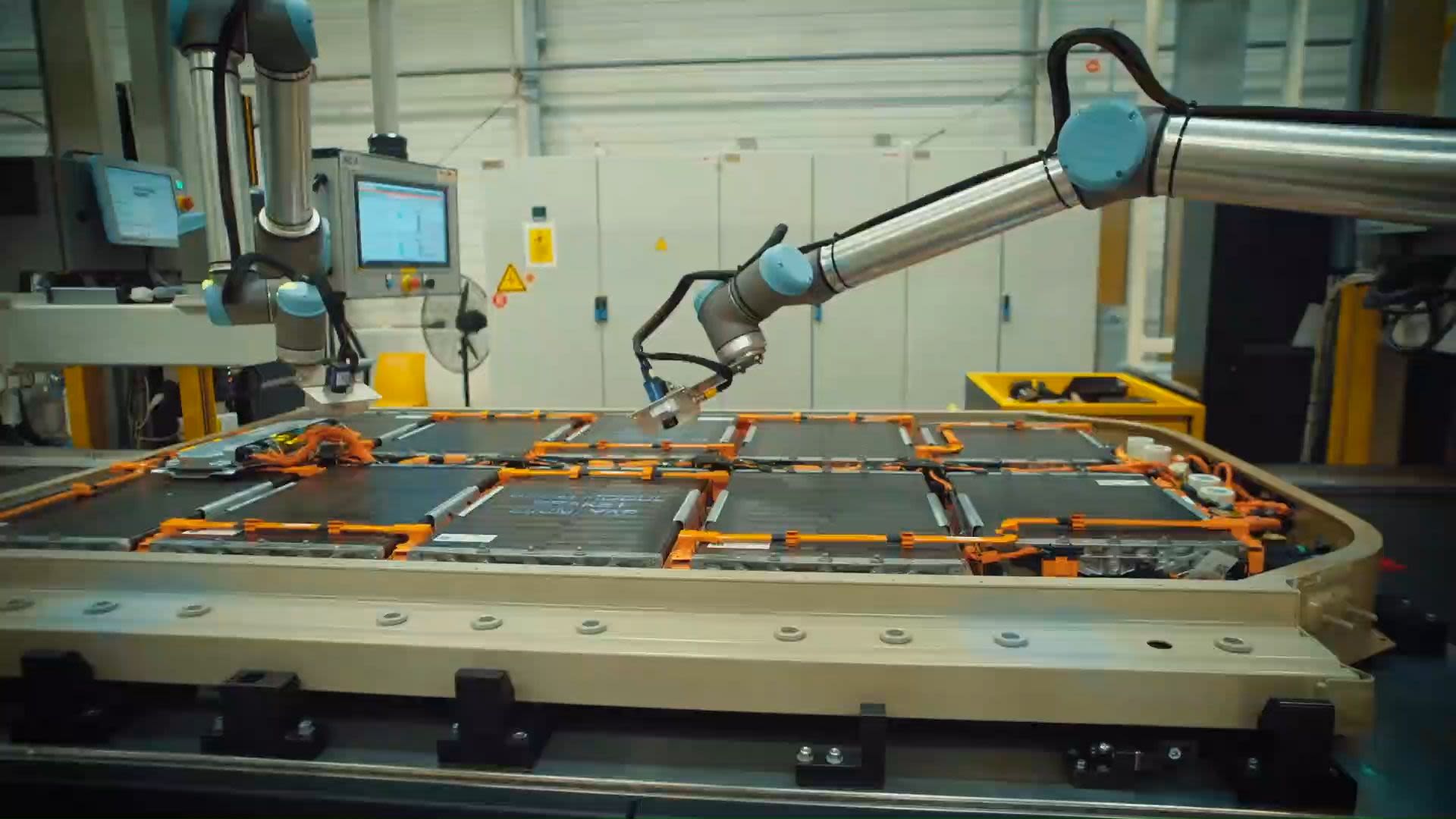

IFC is supporting the shift away from the internal combustion engine. In 2020, it provided a loan worth the equivalent of $150 million to Ford Otosan to help the company launch new models, including electric and hybrid vehicles. (The firm is a partnership between Ford Motor Company and local firm Koç Holding, a common setup in Türkiye.)

Many local players have begun the transition to manufacturing parts for electric vehicles, investing heavily in new technology. But because the rise of electric cars is a relatively new development, 70 percent of the country’s 300 large auto part suppliers have yet to develop the ability to manufacture components specific to electric vehicles, according to IFC research. Türkiye accounts for only 0.07 percent of exported electric-vehicle-specific parts, while Poland, a key competitor, accounts for 22 percent.

For Turkish companies that make powertrain components, like transmissions and axles, failing to prepare for electrification could be disastrous over the long term, said Emmanuel Pouliquen, an auto industry specialist with IFC.

IFC launched a program in 2020 to support smaller local suppliers as they readied themselves for the electric vehicle age. IFC, working with three large international carmakers, helped 10 suppliers refine their corporate strategy, lower their costs, and identify areas for R&D investment. A second phase of the project, with more suppliers, is set to launch in early 2023.

Its goal is to help smaller players break into the fast-evolving electric vehicle supply chain.

“That’s where everything is headed,” said IFC program manager Wim Douw, referring to electrification. “Turkish manufacturers must adapt to assure themselves of a future in this industry.”

Observers say the auto industry still has time to make the transition to electric vehicles and over the coming years they expect parts suppliers and manufacturers will ramp up investments in electrification.

At the turn of the millennium, Türkiye was struggling through a financial crisis and poverty was rampant. An economic boom over the next two decades, driven in large part by manufacturing, would transform the country, doubling incomes and cutting poverty by two-thirds.

That growth has presented a challenge. Rising incomes means the country can no longer compete in lower-value-added industries it once dominated.

“Twenty-five years ago, Türkiye was a center of textile making but today, it cannot compete with low-cost producing countries,” said Dupoizat. “To spur economic growth and graduate to the ranks of the high-income countries, it must continue to boost productivity and climb up the value chain ladder. Electric vehicle manufacturing is a golden opportunity to do just that.”

Published in January 2023

Visuals by Martur, Ege Endüstri and Ford Otosan.