7 Steps to a Zero-Carbon Building

A project in Mexico shows what it takes for a building to go green.

Text, concept and production by Inaê Riveras

Photos and videos by Eduardo De la Cerda

It seems like a new net-zero pledge is announced somewhere in the world nearly every day. As the need escalates for a significant reduction in carbon emissions, multinational corporations, small firms, developers, large cities, tiny towns, and entire countries are all asking the same question:

How do we get to net zero?

Buildings are a good place to start. They consume more than half of the world’s electricity used for heating, cooling, and lighting. They account for more than one-third of energy-related greenhouse-gas emissions when building materials and construction are added. Because of their huge impact, experts agree that without changing how buildings are built and operated, there is no chance of confronting the climate crisis.

Many developers and building owners across the world are responding to the call, even going beyond regulations and standards to build or retrofit existing structures into carbon-neutral buildings. A zero-carbon building does not waste energy, consumes less water, and generates as much energy as it consumes or uses renewables as their energy source.

Transforming a building in this way may seem like an ambitious undertaking—but in León, México, architect Ramon Lopez eagerly took on the challenge.

The Ufficio BJX building was the first certified as EDGE Zero Carbon in Latin America.

The Ufficio BJX building was the first certified as EDGE Zero Carbon in Latin America.

Lopez, general director of Ufficio Arquitectura & Mobiliario, was looking to move his office to a new, bigger location when he came across a 15-year-old family home. When Lopez bought the property, he knew that any changes would have to satisfy local requirements—such as not increasing the building’s footprint.

But as retrofitting work started, Lopez realized that with just a little more money, he could go beyond what was mandated to make the building more climate friendly—and the benefits would outstrip the additional expense.

“We noticed that the difference in investment was very small. Putting in more solar panels instead of the minimum, for example, would represent savings in years to come. Installing more windows would help air circulation, reducing energy consumption,” said Lopez.

He also saw that as an opportunity for his firm to align its business with the values of the brands it sells. His firm is the local representative of office furniture makers including Herman Miller, which was a founding member of the U.S. Green Building Council and whose landmark GreenHouse facility in the 1990s helped popularize sustainable building practices.

The extra touches put the company very close to reaching several requirements of a green building certification, and Lopez decided to pursue that route. First, he followed the steps to receive an advanced certification from EDGE, a green-building certification system launched by IFC whose platform enables project owners to identify the most cost-effective ways to build green. About a year later, the building was certified as EDGE Zero Carbon—the first building in Latin America to achieve such status and the third in the world.

Here’s a step-by-step look at how Lopez retrofitted a 600-square-meter family home into a net-zero office building:

Step 1

Natural ventilation

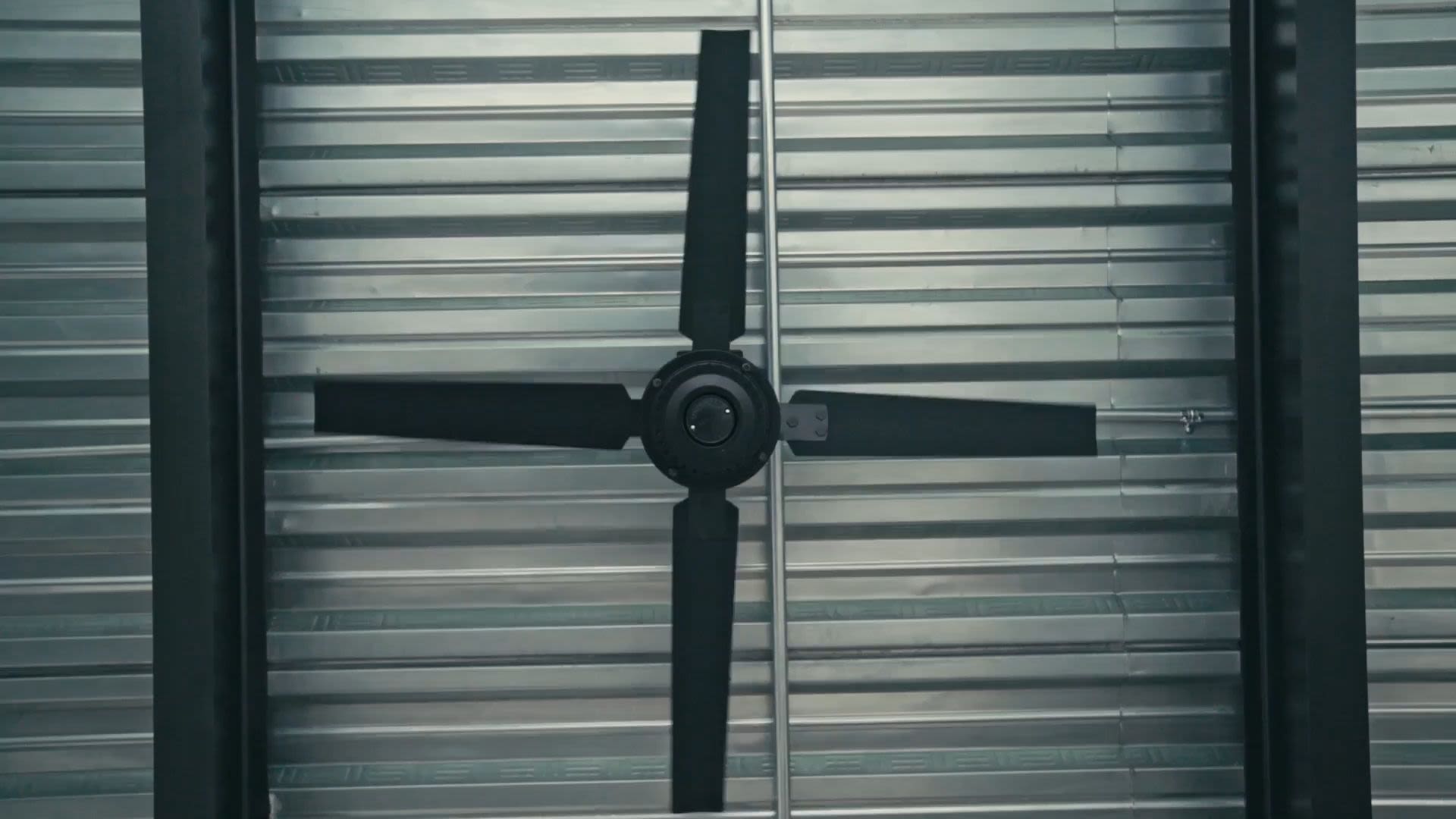

A well-designed natural ventilation strategy can increase comfort in a building by providing both fresh air and by lowering the temperature—reducing the need for air conditioning and maintenance costs. Room size and the number and location of openings all play a role.

Ceiling fans like the ones here increase air movement, making spaces more comfortable by promoting the evaporation of moisture. In colder climates, fans can contribute to better distribute warmer air that tends to rise to the ceiling.

Step 2

Reflective surfaces

The sun is a powerful source of light, but it is also a source of significant heat. Finding the right balance between lighting and ventilation—and between windows and walls on a building façade—helps maximize daylight while minimizing undesired heat transfer.

To compensate for a relatively high window-to-wall ratio in Ufficio BJX, a special kind of coating (called “Low-E”) was used on window glases, explained Deepak Gulati, associate director at the Green Business Certification Inc, the organization that certified the building.

Low-E coatings are microscopically thin metal or metallic oxide layers added to a glass surface to help keep heat on the same side of the glass from which it originates. In warm climates, such as in Mexico, it helps keep the inside of the building cooler.

In some projects, double or triple glazing can improve thermal performance even further.

On walls, reflective paint or tiles contribute to reduced cooling load in air-conditioned spaces and improves comfort in non-air-conditioned spaces. This is important because lower surface temperatures reduce the effect of “urban heat islands,” when natural land cover in cities is replaced by surfaces that retain heat, contributing to higher temperatures, pollution levels, and heat-related illness.

Light colors—such as the white used in the Ufficio BJX—are ideal to maximize reflectivity in warm climates.

Step 3

Energy-saving light bulbs

High-efficiency LED bulbs—which produce more light with less power compared to standard incandescent bulbs—were used in Ufficio BJX to reduce the building’s energy use for lighting. A bulb that doesn’t release heat helps keep the room cooler. It also has a longer shelf-life than that of incandescent bulbs.

The use of lighting controls—such as occupancy sensors or photoelectric sensors that activate light only when natural light is insufficient—also reduces energy consumption.

Step 4

Low-flow faucets

Buildings are big consumers of freshwater resources—mainly through restrooms, heating and cooling systems, and landscaping.

But reducing water use is possible through the installation of low-flow faucets in sinks and efficient toilets. Aerators and shut-off controls in faucets lower water consumption without affecting functionality. Likewise, dual-flush toilets help reduce the amount of water used for flushing.

“Fifteen years ago, people realized that energy was a scarce resource. Now people are becoming aware that water is also a very scarce resource,” said Paola Mendez, from the Energy Efficiency & Energy Advisory Division of the European Investment Bank, which invests in green buildings in and outside the European Union.

Because water requires energy to be treated and distributed to homes and offices, water savings are energy savings as well.

“People are becoming aware that water is also a very scarce resource.”

Paola Mendez, European Investment Bank

Step 5

On-site energy production

Ufficio BJX produces 100 percent of the energy it consumes. The electricity, generated by 18 solar panels at the top of the building, replaces energy that the company would otherwise buy from the grid—often generated from fossil fuels such as coal and natural gas.

Lopez said the investment in the panels totaled about $10,000, which he expects to recover in four years. Since installing the panels, he has been billed only the minimum grid connection fee. He notes the panels have a warranty period of 15 years, which means he’ll enjoy these savings in the long term.

Thanks to supportive regulations and technology improvements, the cost of solar panels has dropped by almost two thirds in the past decades. Many types of solar photovoltaic systems are available today, using different technologies with varying levels of efficiency.

Buildings without open space for panels may buy off-site renewable energy from the electrical grid where available—which may be more accessible and affordable for some consumers than on-site generation.

Step 6

Lower-carbon materials

The energy contained in construction materials is an important aspect of a building’s total carbon emissions. Embodied energy is the energy required to extract and manufacture the materials required to construct and maintain the building—from its extraction to processing to transportation.

In addition to opting for materials that require less energy to be made, existing materials can be reused. To be classified as reused, the material—including floor slabs, roof construction, walls, flooring, window frames, or insulation—must be more than five years old. It does not have to have been sourced from the project site.

In Ufficio BJX, half of the walls were kept from the original building. Lopez added materials considered more environmentally friendly, such as composite in-situ concrete and steel decking.

Step 7

Native plants

Although not necessary for the certification process, Lopez chose to use native plants for landscaping around Ufficio BJX. These plants have many benefits: environmental, health, ecological, and economic.

Native plants do not require fertilizers or mowing and need fewer pesticides than lawns or none at all. They require less water and help prevent erosion while providing shelter and food for wildlife.

Certification: Good, Better, Best

As the urgency to limit the rise in global temperature grows, so have the certification systems to rate green buildings.

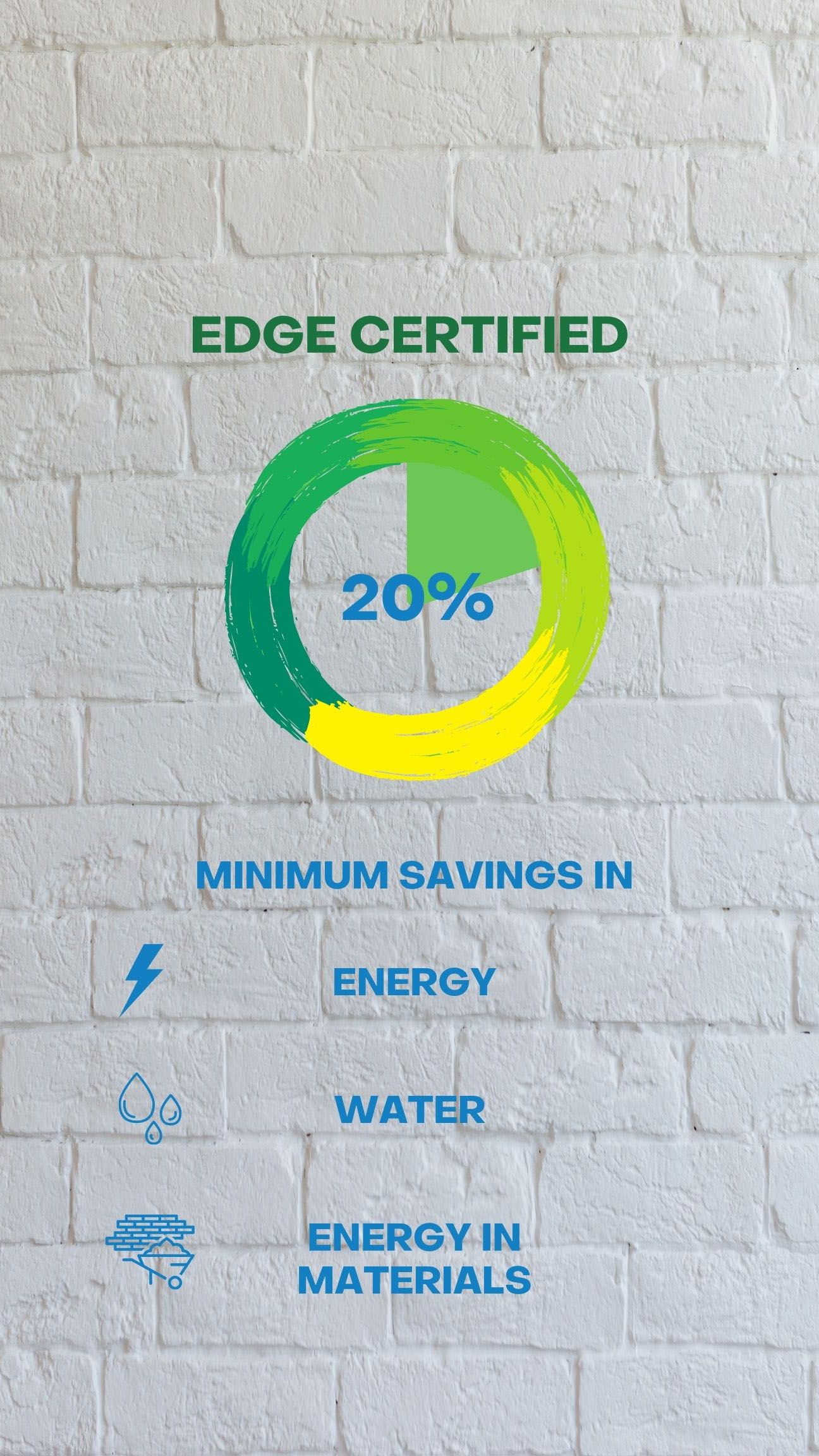

A few years ago, certifications like EDGE were limited to basic requirements: a 20 percent reduction in three categories: energy, water use, and embodied energy in construction materials.

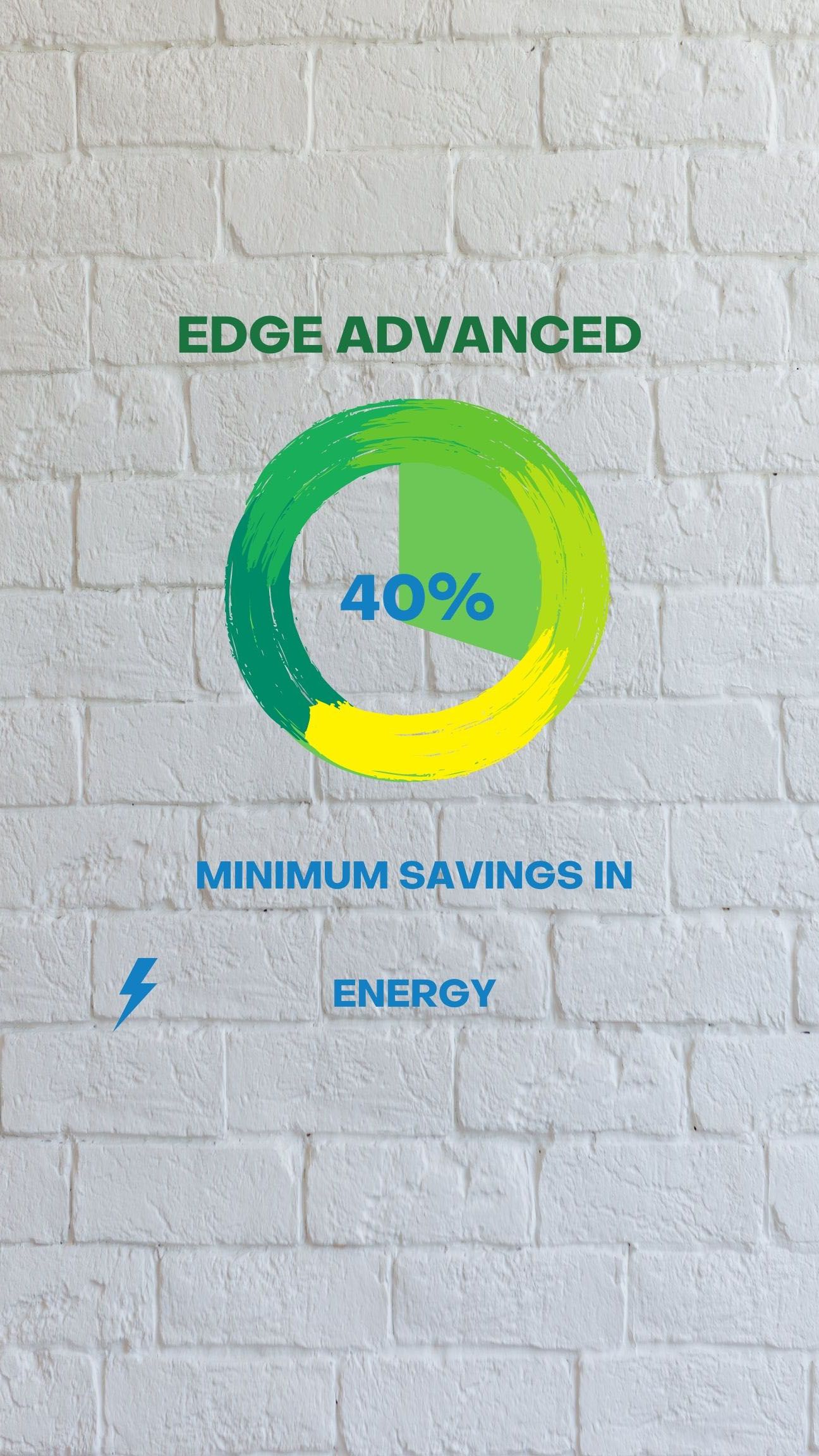

But as the urgency to implement climate-smart solutions grows and governments and companies adopt more ambitious targets, new certifications set the bar higher.

EDGE Zero Carbon certification starts with a 20 percent reduction in water use and in embodied energy in materials. In addition, a building must comply with on-site energy savings of least 40 percent and have 100 percent of its energy emissions neutralized either through renewables or carbon offsets.

Organizations like the World Green Building Council have been calling on the signatories of the Advancing Net Zero agenda—including companies, cities, states, regions, and organizations—to reach net-zero operating emissions in their portfolios by 2030, and for all buildings to be net zero in operations by 2050. This will be critical to limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius by mid-century.

To achieve this target, 3 percent to 5 percent of all existing buildings would need to be renovated each year until 2050.

“We’re seeing more and more pledges to become zero carbon, from large players to small players, including major energy companies that have come to us asking what they could do,” said Ommid Saberi, senior green building specialist at IFC. “It’s becoming increasingly clear [to everyone] that we have very limited time to change the trend in emissions.”

Lopez, who now spends workdays in his zero-carbon office, wouldn’t change anything about the journey to create an energy-efficient workspace. Even though he says that many people questioned the retrofit process and thought the certifications were an unnecessary expense, they are “an investment in the future.”

“You can’t ignore what’s going on in the world,” he said. “And you don’t need to have a big building to start the change.”

“It’s becoming increasingly clear that we have very limited time to change the trend in emissions.”

Ommid Saberi, IFC

Infographic by Rayna Zhang.

Published in November 2021